But what about sleep?

As drink drive limits return to the headlines, the conversation is rightly focused on impairment, judgement and public safety. Alcohol is regulated because we understand a simple truth. Impaired people are not safe behind the wheel.

But alcohol is not the only thing that impairs judgement.

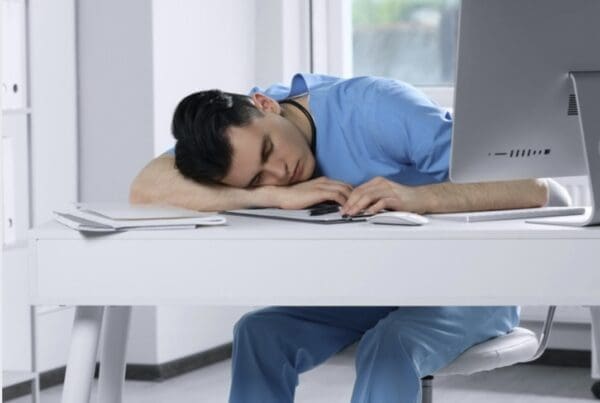

Sleep deprivation does too.

And unlike alcohol, it is still largely invisible, unmeasured and unregulated.

What makes this especially concerning is that people who are chronically sleep deprived often do not realise how impaired they are. Tiredness reduces insight. It creates false confidence, slower reactions and poorer decision making, while convincing the person experiencing it that they are coping just fine.

This is not opinion. It is well established in road safety, occupational health and cognitive research.

Why alcohol and eyesight are taken seriously

Alcohol is treated as a safety issue because it is measurable. There are clear legal limits, roadside tests and public messaging. If you drink, you are expected to question whether you are safe to drive.

The same logic is now being applied more broadly. Proposed driving reforms reported by ITV News include lowering the drink drive limit, mandatory eyesight checks for drivers over 70, and other measures aimed at reducing deaths and serious injuries on the road. These changes reflect a clear policy shift towards prevention. Where impairment can be measured, it is regulated.

Because alcohol and eyesight are visible and testable, they are taken seriously.

Sleep deprivation, despite causing comparable impairment, has none of these safeguards.

There is no agreed threshold for tiredness. No reliable roadside test. No clear public messaging beyond vague advice to “take a break”. And no consistent expectation that employers should manage sleep related risk in the same way they manage alcohol or eyesight risk.

The problem with the data

In UK collision statistics, fatigue is recorded in only a small percentage of serious and fatal crashes. But road safety organisations are clear that this significantly underrepresents reality.

There is no reliable way to test for tiredness after an incident. Drivers rarely identify themselves as fatigued. Investigations often default to terms such as inattention, loss of control or error. The impairment disappears from the record.

When fatigue is analysed more carefully, using time of day, sleep opportunity, work patterns and crash characteristics, it becomes clear that it plays a role in far more serious and fatal collisions than official figures suggest.

This undercounting is not evidence that fatigue is rare. It is evidence that we are not equipped to measure it properly.

Impairment is impairment

Extended wakefulness affects reaction time, attention, emotional regulation and decision making. It increases risk taking and reduces the ability to accurately assess danger. In many cases, people who are severely sleep deprived genuinely believe they are functioning well.

This is exactly what makes it dangerous.

We do not rely on people who have been drinking to self assess their impairment. We recognise that judgement is already compromised. Yet with sleep deprivation, we do exactly that. We trust people to decide whether they are safe, even though tiredness itself affects the ability to judge risk.

The workplace contradiction

Most workplaces have clear policies around alcohol. Many also assess eyesight and fitness for work in safety critical roles.

Very few workplaces have equivalent policies around sleep.

Long hours, shift work, overnight work, early starts and chronic sleep loss are normalised. Exhaustion is framed as resilience, commitment or just part of the job. When something goes wrong, responsibility sits with the individual rather than the system that created the conditions for impairment.

Yet sleep deprivation increases accidents, errors, sickness absence, burnout and long term ill health. The evidence is not new. What is missing is action.

Why this matters now

If the principle behind drink drive limits and eyesight checks is prevention rather than punishment, then sleep cannot remain excluded from the conversation.

Impaired judgement does not become less dangerous because it is caused by work patterns, caring responsibilities or cultural expectations. The risk is the same. The consequences are the same.

Until sleep is treated as a core safety issue rather than a personal lifestyle choice, we will continue to overlook one of the biggest contributors to avoidable harm on our roads and in our workplaces.

And we will continue to describe those outcomes as accidents, when they are anything but.

So what can we do about it?

The answer is not telling people to “sleep better” and hoping for the best. In the same way that drink driving prevention is not solved by simply telling people to “be sensible”, sleep related risk needs structural, not individual, solutions.

First, we need to name sleep deprivation for what it is: a safety issue. Not a lifestyle choice, not a resilience problem, and not a personal failing. If impaired judgement is a risk, then the cause of that impairment matters less than the outcome.

Second, sleep education needs to be normalised in workplaces. People are rarely taught how sleep works, how shift patterns affect the body, how chronic sleep loss builds over time, or how impairment shows up before people notice it themselves. Without education, we are asking people to manage a risk they do not fully understand.

Third, organisations need to recognise fatigue as a predictable and preventable risk. That means looking honestly at workload, scheduling, shift design, recovery time and expectations around availability. In the same way that alcohol policies exist to prevent harm before it happens, fatigue risk management should focus on prevention, not blame after the fact.

Finally, we need clearer public messaging. Just as we now accept that drinking and driving do not mix, we need to move away from the idea that being exhausted is something to push through or quietly endure. Driving while severely sleep deprived, or working in safety critical roles without adequate rest, should be treated with the seriousness it deserves.

None of this requires new science. The evidence already exists. What is missing is the will to apply it consistently.

Until we do, we will continue to place responsibility on individuals while ignoring the systems that create impairment in the first place. And we will continue to accept preventable harm as an unfortunate but inevitable part of modern working life.

Here is a link to the ITV news article.

https://www.itv.com/news/2026-01-07/lower-drink-drive-limits-and-eye-tests-for-over-70s-proposed-driving-reforms